Blimey, it’s the end of June, so that means that 50 years ago, I was already well into my stint as a general dogsbody at a furniture trade exhibition in a building which would later become the Air and Space Gallery of the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, and which has just now become a trendy food hall. I’d completed my second year at Leeds, and exercised my franchise for the third time, having voted in the two elections of 1974. This time, we were voting in the 1975 Referendum on membership of the EEC. We voted overwhelmingly to stay….

Anyway, to return to the business of the Leeds English degree of half a century ago. At the end of the first year, we took exams in various aspects of English, and in our subsids of course. Having passed them – we weren’t told what marks we’d got, nor did we receive any feedback – we were then set fair for part II of the degree, where we would be concentrating solely on English for two years. We had to choose which “scheme” we would follow. Four options were offered. Scheme A was largely based on the Anglo-Saxon element of the first year; scheme B was biased towards medieval studies; scheme C was a broad-based English Lit programme; and scheme D was the English Lang programme. There were some elements common to all schemes, but each had a definite character. In common with about two-thirds of my peers, I chose scheme C. There were about 100 students in my cohort, so I suppose roughly 60 or 65 were on scheme C with me. In this post and the ones that follow, I’ll explore what that entailed.

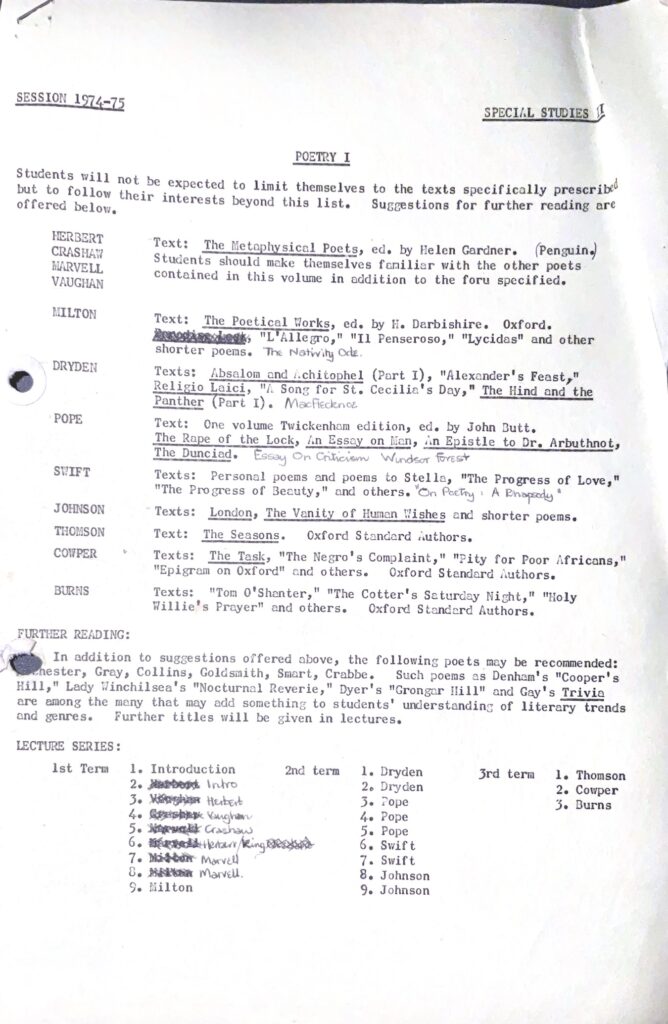

We had lectures which were designed to give us a foundation in the study of literature, and the courses were very much organised on a historical model, so that in this part I year, we were studying texts from the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century. The core courses were on Poetry and the Novel. For the Poetry course, we revisited quite a bit of the material we’d encountered with Ken Severs, but with many additions. Here’s the handout we were given at the first lecture. Note that we were required to read nine texts, plus additional reading, for just this one element of the programme.

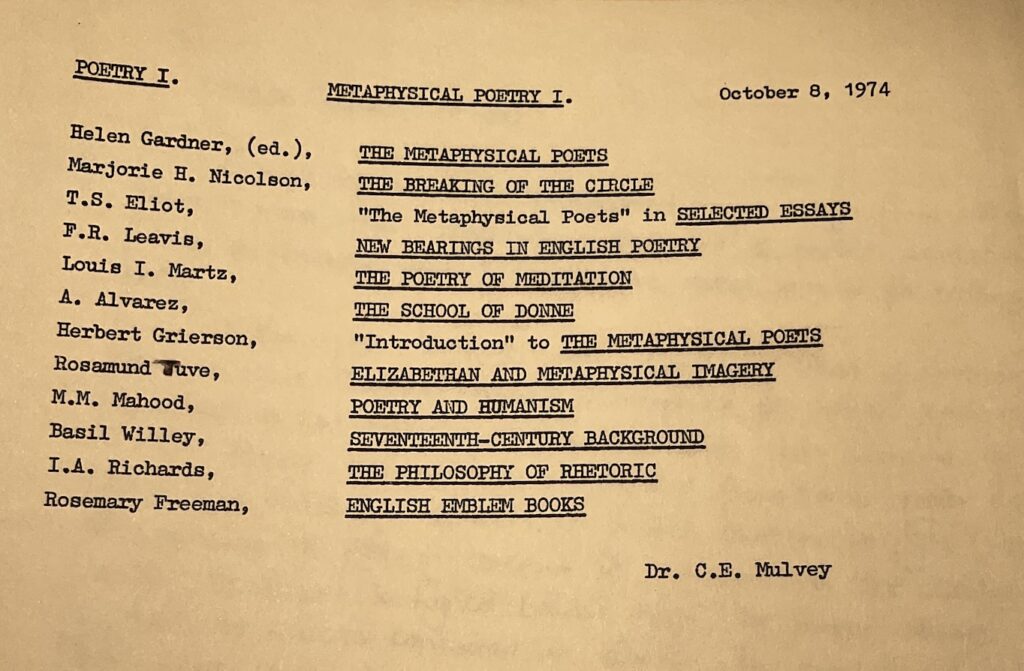

Just one lecture on Milton, you’ll notice, because we had an entire course on Milton, about which I’ll write at a later date. Unusually, for the section of the course on Metaphysical poetry, we were given another handout, and that handout had our lecturer’s name appended to it, which means that I was able to trace his further career.

Dr Mulvey, I am pretty sure, is Christopher Mulvey, who had a distinguished career as an academic specialising in American literature. In recent years, he has been involved in something called The English Project based at Winchester, where he is still Emeritus Professor. He seems to have stayed just one year at Leeds, but we found his lectures engaging, rigorous and informative. Certainly, following up his lectures in tutorials, and writing essays informed by them, we felt that we were engaging at a higher level than previously. Most of us had encountered the Metaphysicals, if not at A level, then in the first year. But the eighteenth-century figures, except for Pope, were probably new to the majority of students. All the poets studied were men, of course. It was fifteen years later that Roger Lonsdale’s ground-breaking anthology opened up the vast range of historic poetry by women for serious study. The early seventies were, I think, the last years of this kind of traditional degree. Already, the canon was being challenged, and something called Literary Theory was beginning to insinuate itself into the syllabuses of the more radical campuses, years after it had been chic in France. But we remained traditional at Leeds, and that ensured we had a very sound grounding in the subject – or at least in the masculine side of it.

![]() Scheming through the second year by Dr Rob Spence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Scheming through the second year by Dr Rob Spence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.