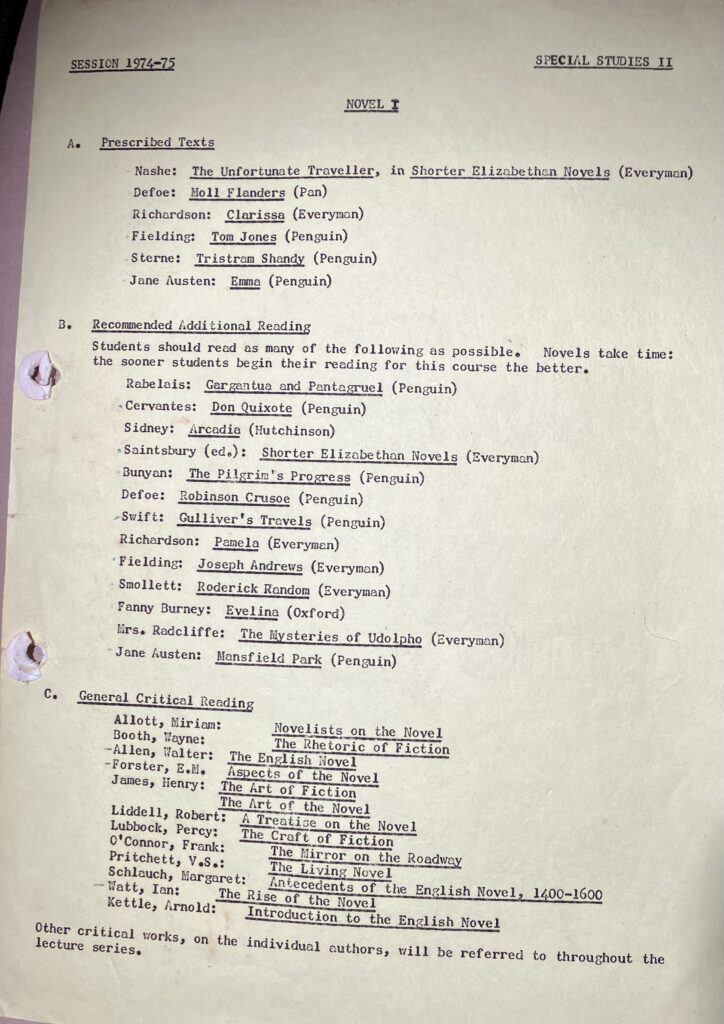

Our novel course in 1974-5 took us from the early seventeenth century to the early nineteenth. Six substantial texts were prescribed, and a good many others recommended. Here’s our reading list from that year.

I think I read most of the novels listed here. All of the key texts, of course, and quite a few of the additional ones. I avoided Don Quixote until a couple of years ago, and I managed only small portions of Gargantua and Pantagruel and Arcadia. Otherwise, a clean sweep. Wayne C. Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction was an invaluable companion, as was Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel. Both of those critical works, it seems to me, stand up very well now, well over sixty years after they were first published.

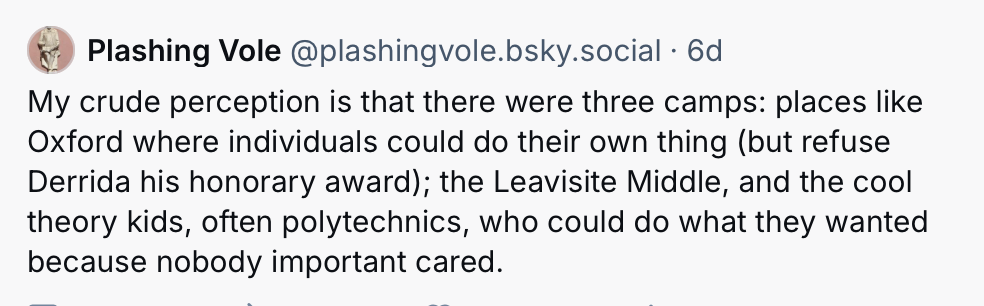

Our course consisted of weekly lectures, which might or might not be backed up in the general tutorial, according to the whim of the tutor. This system, whereby the lecture programmes were distinct from the weekly tutorial, certainly kept us on our toes. We might have attended a lecture on, say, Moll Flanders, but our tutor would announce that we were discussing Tom Jones next time, so we had better read that before our next meeting. Our lectures were delivered by Douglas Jefferson, who was at the time, effectively, the head of department, I think. Not that we were aware of his status then. I think I remember an office door bearing the name A. Norman Jeffares, who was, until 1974, the head of department, but whom I never encountered. Jeffares was a noted Yeats scholar, and a kind of literary entrepreneur. He was responsible for launching York Notes, the UK equivalent of Cliff’s Notes, whose early volumes were often written by Leeds scholars, including Loreto Todd, of whom I wrote previously. Jeffares died in 2005, and this obituary gives an illuminating account of his life. The obit was written by W.J. McCormack, about whom I will write in a future post. Its portrayal of the department at Leeds confirms my memory that the staff did not engage much with the literary theory that was fashionable at the time. I had an exchange with some Bluesky pals on this, and Plashing Vole defined the 1970s state of play perfectly:

Leeds definitely seemed to be the “Leavisite middle” and Leavis himself will feature in these reminiscences in due course.

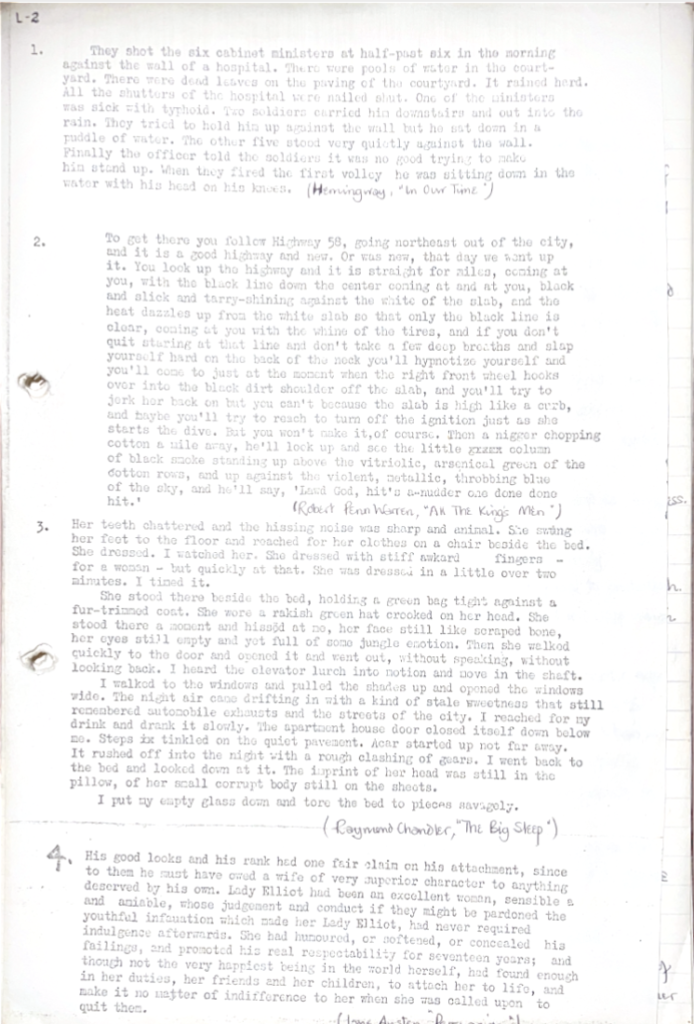

But back to the novel, and D.W. Jefferson, who was universally liked. I think of him now as a rather portly man in late middle age, not unlike Ford Madox Ford in appearance, with a pleasant demeanour and an easy lecturing style. He was a Leeds stalwart, spending his entire career there, excepting war service. I was delighted to come across this Festschrift (perhaps better described as a memorial volume) containing some of his very wide-ranging work. (And I think one of the editors was a contemporary of mine at Leeds.) Jefferson’s easy grasp of the subject made the lectures a very pleasant experience, and was doubtless the main reason that I was enthusiastic to read so many of the texts he mentioned. I see from my notes that it was week 5 before we got down to cases and considered Nashe’s The Unfortunate Traveller. This was to allow for a consideration of the language of the novel, realism and morality in the novel. Jefferson used a technique that I adopted myself as a lecturer, which was to give us contrasting snippets to provoke observations on style, language, syntax etc. I have one here:

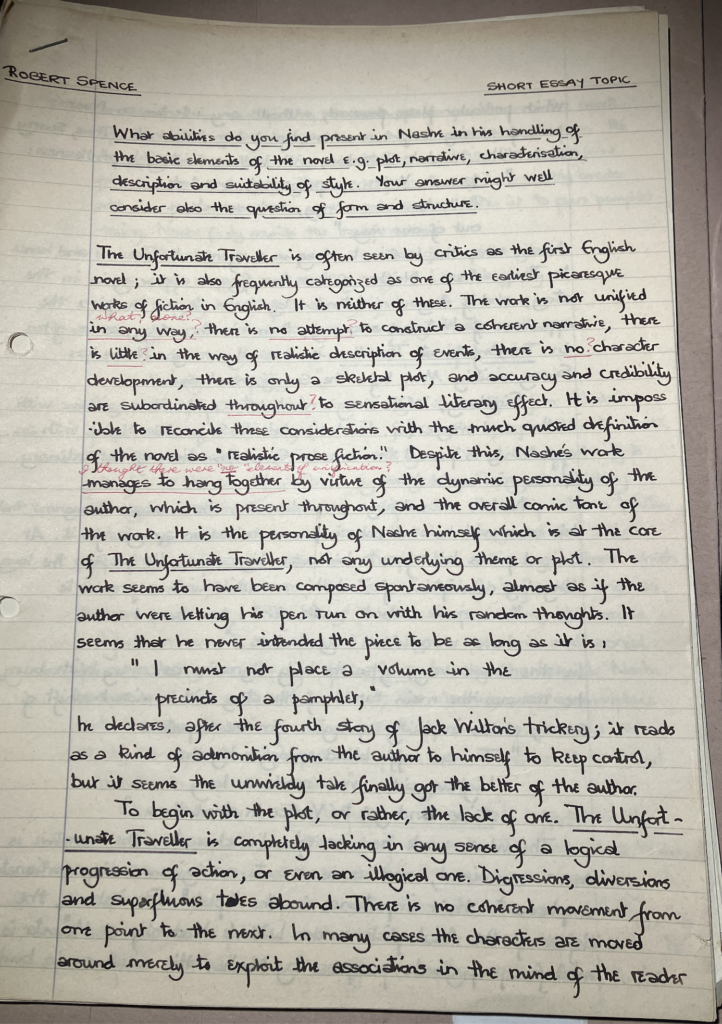

So, even though our focus was on the novels of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, we were considering wider questions of form and expression in the novel as a genre. I think the earliest novel I had read before this course was Persuasion for A level. So Nashe, the picaresque and especially Sterne were revelatory, and I enjoyed immersing myself in the way the novel shaped itself in its formative years. I find that I wrote essays on Nashe, Fielding and Richardson from this course, and extensively on Sterne in another course which will be the subject of a future post. Here’s the first page of my essay on Nashe:

My tutor is already getting a bit exasperated by it, from the early red ink comments. The final, actually rather generous comment reads, in part: “This is a light-hearted and rather witty treatment; easy and pleasant to read, with a number of intelligent comments, but rather thin.” The comment, which goes on for a whole page of A4, highlights a number of failings, but doesn’t totally condemn my effort. Later essays were more serious in tone, and attracted less flak.

We felt extremely well-catered for by this course, from which I gained a lifelong affection for Sterne, who became the subject of my MA thesis, and for the early novel in general. When I did eventually read Don Quixote decades later, I recognised so much of what the early English novelists had learned from Cervantes.

![]() Novel Discoveries by Dr Rob Spence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Novel Discoveries by Dr Rob Spence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.